Sara Golcman Bedzow was born July 28, 1926, in Leopoldów, Poland, outside of Warsaw, to Feiga and Jacob Golcman. Her Orthodox family owned the largest grocery store and bakery and in the area, and together with her seven siblings and two parents, she enjoyed a happy childhood. All of that changed when acts of antisemitism shook her village in 1938, followed shortly by the German invasion of Poland in 1939. Soon, Leopoldów became a ghetto. Sara and her younger sister, Gittel, were subjected to forced labor in the fields while the rest of the family was home trying to survive.

Starting at a young age, Sara was forced to make courageous decisions in the face of danger. One brisk winter day in 1941, German soldiers searched the Golcman’s house. “We had to give away all the furs, all the jewelry, and all the possessions that we had,” Sara remembers. Without a word, Sara hid her mother’s jewelry beneath a stove burner. “In my mind, it was something that I didn’t want somebody to be responsible for. If they’re going to hit somebody or going to force somebody, they would tell. If only I knew, nobody would talk.” While the soldiers were preoccupied with searching the house, Sara smuggled the Sefer Torah to the outside toilet through the back door. She lifted the lid and placed the wrapped Torah into the frozen toilet before quickly returning.

“At that moment, I knew when they saw the Sefer Torah, they were going to burn it instantly. It wasn’t even a question. And they could harm the whole family because we had a Torah.” Once the soldiers left and it became dark, Sara went to the toilet to retrieve the Torah, hoping no one saw her. However, not long after, the soldiers returned with questions. “I didn’t hide anything. I had to go to the toilet,” she told them. The soldiers were about to take her away when a Polish man with the Germans advocated on her behalf. “What can this little girl do?” The soldiers glanced at Sara as if agreeing, then left her.

Sara and her family lived in the ghetto until May 7, 1942, when it was liquidated. Sara and Gittel were working in the fields when they saw their family being taken away. That was the last time Sara saw many family members who were murdered at the Sobibor Concentration Camp. By nightfall, Sara and her fellow workers were locked in a barn. “I said to the girls, ‘We have to get out and run away.'” They climbed on top of each other to reach the loft, Sara managed to climb out and open the barn door. “We cannot stick together,” she told the girls. “We have to run away, everybody in different directions. Then somebody will survive.”

Sara and Gittel ran into the forest. They reached the house of a wealthy Polish man well known to the Jewish community – Stahurski – who dedicated himself to helping fellow Jews. There, Sara was reunited with her brother, Josef. They hid in Stahurski’s attic for a few days, along with ten others, until their brother Herschel met them there. Together, the four siblings fled to their uncle’s house in Yadamov, soon finding themselves on the cusp of another liquidation. The siblings decided that the brothers would stay at the labor camp, and the girls would return to Stahurski. But Gittel would not budge. “I walked over to Gittel, and I begged her to come … she was crying, and she didn’t want to go for love or money. She said, ‘Do whatever you want. I am not going. I don’t care.’ I had no choice. I picked myself up, and I went by myself.”

Sara wandered through the woods by herself until morning when she finally arrived at Stahurski’s home. The next day, her brother arrived with news that the ghetto in Yadamov was liquidated a day early. A day later, Herschel came without Gittel. However, it was no longer safe to stay as searches were frequently happening. They fled to a Polish friend of their father’s, a farmer, whose family hid them under their barn floorboards. They hid until contact was made with the Jewish partisans who discovered that Sara’s brother, Josef, had served in the army. He joined the partisans who blew up trains and fought the Nazis with whatever they had.

In February 1944, another partisan group approached the barn where Sara was still hiding. They were searching for food when the Armia Krajova, Polish Home, discovered that the partisans were there. A shoot-out ensued, causing the straw in the barn to catch on fire. “The stable boy was afraid that we’d get burned. He came in. He said, ‘You have to run away.’”

He opened the door, and Sara, along with other girls in hiding, emerged into the cold night as the stable burned. A member of the AK recognized Sara from living in Leopoldów and exclaimed, with a gun in hand, “You are Jewish girls.” Sara ran hard. She tumbled into the fresh snow as the other girls trailed behind. The man did not see where she fell, but immediately noticed the other girls who were pleading with him, “Why? Why? Why are you killing us?” Then Sara heard gunshots followed by a deathly quiet. Sara waited an hour before running. She ran the whole night until finding a farm where the residents hid her in piles of hay. Sara knew the partisans would try to find her, and the next day her brother arrived along with two fellow partisans. With no shoes, and wearing only a nightgown, on a frigid February night, they carried her to another farmer’s house who supported the partisans.

After a brief respite, the two siblings reunited with their partisan unit, the Glowver Forest Otriad. While with the partisans, Sara helped around the camp. “I used to melt the snow and wash the clothes for them. I did the chores.” On June 17, 1944, the Russians advanced and pushed back the Germans as they moved toward Warsaw. Sara and around thirty partisans rode on the Russian trucks to Lublin. Sara lived in the forest and served with the partisans from 1942 until the end of 1944. She eventually made her way to Lodz toward the end of the war.

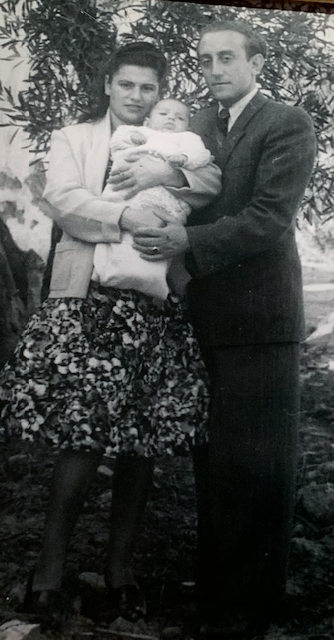

In Lodz, Sara, who was now an orphan, met her husband, Chonon (Charles), who had fought as a partisan with the Bielski Brigade. Together with around 2,000 other Jews, they made their way by foot from Poland to the Displaced Persons camp in Garlasco, just outside of Turin, Italy. Charles and Sara were married there on March 8, 1946, and welcomed their first daughter, Frances, in 1948. Aided by HIAS, they received visas to Montreal, Canada, where they settled in 1949.

Sara and Charles built a wonderful life. Two Holocaust survivors came to Montreal together with Charles’ mother, Chasia, and his brother Benjamin. They worked seven days a week to build a business from the ground up and became successful and philanthropic international real estate developers.

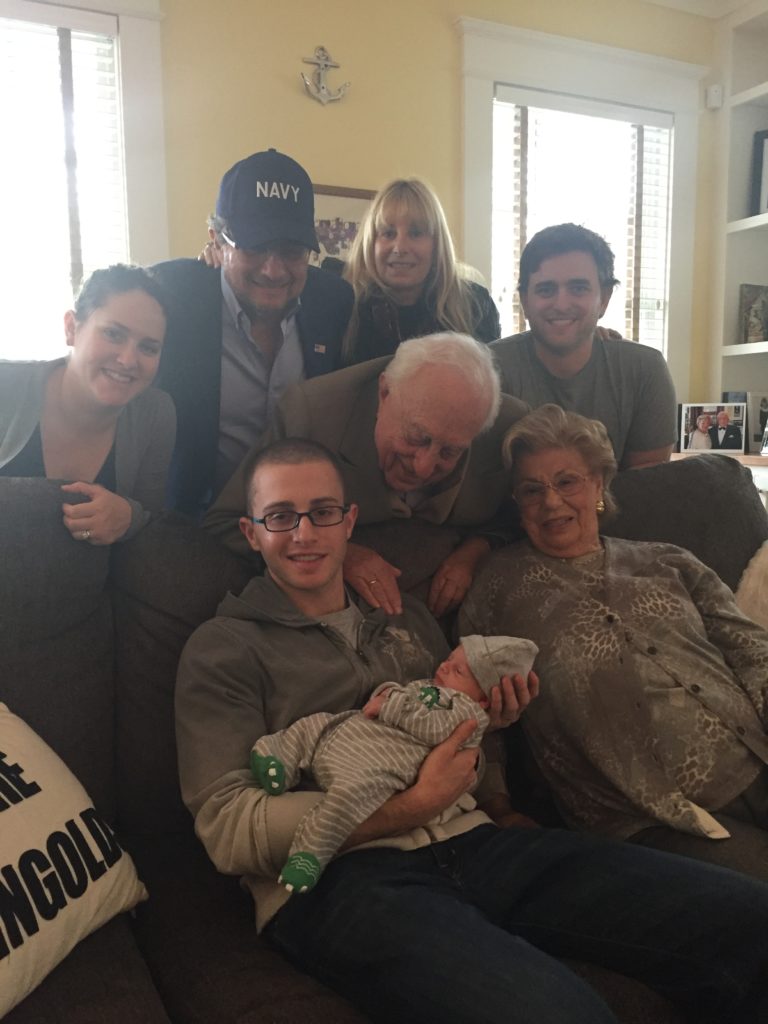

Sara and Charles’ most essential values perpetuated to their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are to work hard, pursue advanced education, give tzedakah and be mensches, and always support Israel. They are blessed with three children, Fran, who is married to Howard Shapiro; Michael, married to Caryn, and Esther, who is married to Dr. Allan Feingold. They are also blessed with eight grandchildren, ten great-grandchildren, and one due in March 2021. All of their grandchildren hold professional graduate degrees, and among the eight there are, one doctor, one rabbi, a Lieutenant in the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General Corps, two attorneys, one chef, one educator, and one businessman.

As life-long Zionists, Israel holds a special place in Sara and Charles’ hearts, and they are generous, strong supporters of the country. They have made more than 20 trips there, including one with each grandchild to commemorate their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs. Their granddaughter Michal Oshman, her husband Michael, and great-grandchildren Raaya and Gavriel, made aliyah in 2016.

Sara’s husband, Charles Bedzow, is JPEF’s Honorary International Chairman, and granddaughter Lauren Feingold, is a member of the JPEF, Board of Directors. You can view Charles’ biography and video testimony at https://www.jewishpartisans.org/partisans/charles-bedzow.